Scientists estimate that cats have lived with us for at least 9,000 years, and surveys show that many of the 45 million households in the U.S. today consider their 96 million cats bona fide members of the family. Yet after all these years, how well do we really understand cats?

It turns out not that well, says Katherine Houpt, VMD, Ph.D., animal behaviorist and professor emeritus at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. Cats’ body language is daunting for many of us to interpret, particularly because of their anatomy.

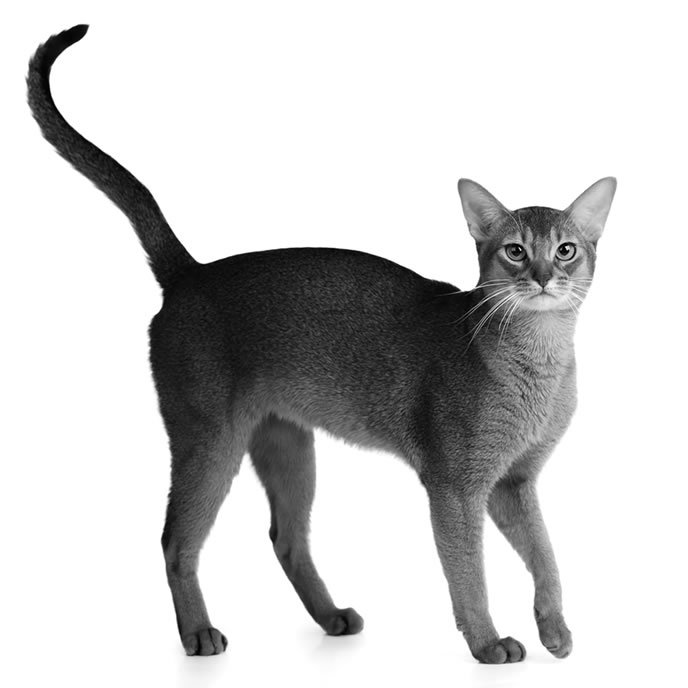

Photo: Bigstock

Facial Changes. “One reason may be that cats have more flattened faces, so it is difficult to see how their face changes,” Dr. Houpt says. “Also, although both cats and dogs have furry faces, somehow the cat seems to hide more change in muscle tone. Cats have longer and fluffier fur, and so if you are looking at a shorthaired dog, for example, he may frown and you can see that. But you can’t see it on your cat.”

A primary reason that humans and cats haven’t evolved to a point of mutual understanding: Cat don’t perceive humans as different from themselves, according to author John Bradshaw, Ph.D., a scholar of animal-human interaction. He says his research shows that the behavior cats exhibit toward us is the same they show to other cats. “Putting their tails up in the air, rubbing around our legs and sitting beside us and grooming us are exactly what cats do to each other,” Dr. Bradshaw says.

Cats use several methods of communicating with us, including sounds, such as purring. Scent is important, too, Dr. Houpt says. Olfactory communication might include urine marking or rubbing scent glands on various objects and people, although cats who like to rub against their owners aren’t necessarily showing signs of affection. They’re marking their territory.

Photo: Bigstock

Telling Signs. By far, however, the most telling method of communication is body language, says Germain Rivard, DVM, IPSAV, Ph.D., a former veterinary behavior resident at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. “Animals communicate among themselves using chemical signals, but body language is the most important way of communicating during social interactions, whether between themselves or with humans,” Dr. Rivard says.

Most of us can easily identify the body language of a potentially defensively aggressive cat — think the arched back of the classic Halloween black cat, Dr. Houpt says. However, interpreting the signs of a stressed or scared kitty can be trickier. Vocal cues can reveal some emotions, but movement is more significant, especially in conveying subtle moods such as annoyance or more serious ones such as being frightened, stressed or in pain.

“Because cats in pain usually hide, you won’t see body postures that might indicate discomfort. A cat in pain will lie on his chest with his tail curled around him,” Dr. Houpt says.

The most commonly misunderstood signs: tail wagging and an exposed belly. Here are keys to interpreting feline body language:

The Eyes

Calm eyes with small pupils: a relaxed, happy cat.

Dilated pupils looking almost all black: fearful and potentially aggressive. Pupil size is revealing because cats have pupils that can change sizes dramatically, Dr. Houpt says.

A direct stare: a threat to other cats not unlike staring by humans.

The Ears

Perked and forward: an alert and content cat.

Flattened: a definite sign of fear. “The more afraid a cat is, the flatter his ears will become until it looks as if you put a saucer on top of his head because the ears are squished down so far,” Dr. Houpt says.

Perked and swiveling: Ears on the move indicate that a cat is attentive and taking in the sounds around him.

Photo: Bigstock

The Voice

Growling, hissing or spitting: Best avoid this cat.

Meows: a sense of urgency for food or attention.

Purring: a sign of contentment in a normal situation. However, Dr. Houpt says, “It can mean other things, as well, such as anxiety.”

Body Posture

Lying on the side: A relaxed cat lounges on his side with his legs outstretched.

Lying on the back: This cat is comfortable in his surroundings.

An exposed belly: no petting, please. “In some cases, it is a sign of submission to other cats, but it doesn’t mean he wants to be petted,” Dr. Houpt says. “Some cats will tolerate it or might even like it, but a lot of cats feel like it’s an invitation to fight if you put your hand on their belly. They will scratch or attack you with all four legs, and maybe even bite you if you try to do so.”

Photo: Bigstock

Arched back: This can be accompanied by the hair standing on end. “The cat makes himself tall to make potential predators think he is more of a threat,” Dr. Houpt says.

Sitting like a sphinx: The cat is alert and possibly stressed. On the other hand, “If your cat is sitting like a meatloaf, with his paws tucked underneath his body, that is not a happy cat,” Dr. Houpt says.

Crouching: Cats take this position before they spring on their prey.

The Tail

Relaxed with smooth hair: a contented cat.

Wagging: Unlike dogs, cats who appear to be wagging their tail are more likely bothered than happy. “Tail movement in cats is not well understood by people,” Dr. Houpt says. “If a cat lashes his tail, he’s annoyed.” And, the faster a cat’s tail is wagging or thumping, the more irritated he is.

Standing straight up: You’ve got a scaredy-cat on your hands. “The fearfully aggressive cat has sort of a bottle-brush tail,” Dr. Houp says.

Photo: Bigstock

The Paws

Swatting: offensive and defensive aggression.

Kneading: A relaxed cat will move his paws in a motion that resembles kneading bread dough. It’s probably the motion kittens used to massage their mother’s breast to stimulate milk.

Failing to recognize feline body cues often leads to disastrous results for both humans and cats. A 2014 study by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand found that 30 percent of people bitten by cats required hospitalization to prevent severe bacterial infections from spreading.

Cat bites seem to be reported less frequently than dog bites, though it’s not clear if they occur less often. “It’s possible, although a lot of cat bites are predatory in occurrence,” rather than the result of fear or aggression, Dr. Houpt says. “So you have a cat who is stuck in the house, which is good, because he will live longer, but he has evolved to catch 12 mice a day. Instead of jumping on mice, he jumps on your ankles.”

She recommends providing cats with more predatory play time so they can fulfill their instincts. “Just buying the cat a catnip mouse is not going to do it,” Dr. Houpt says. “There are a zillion toys available, but the best ones are the fishing pole ones that you can dangle and then the cat can leap after it.”