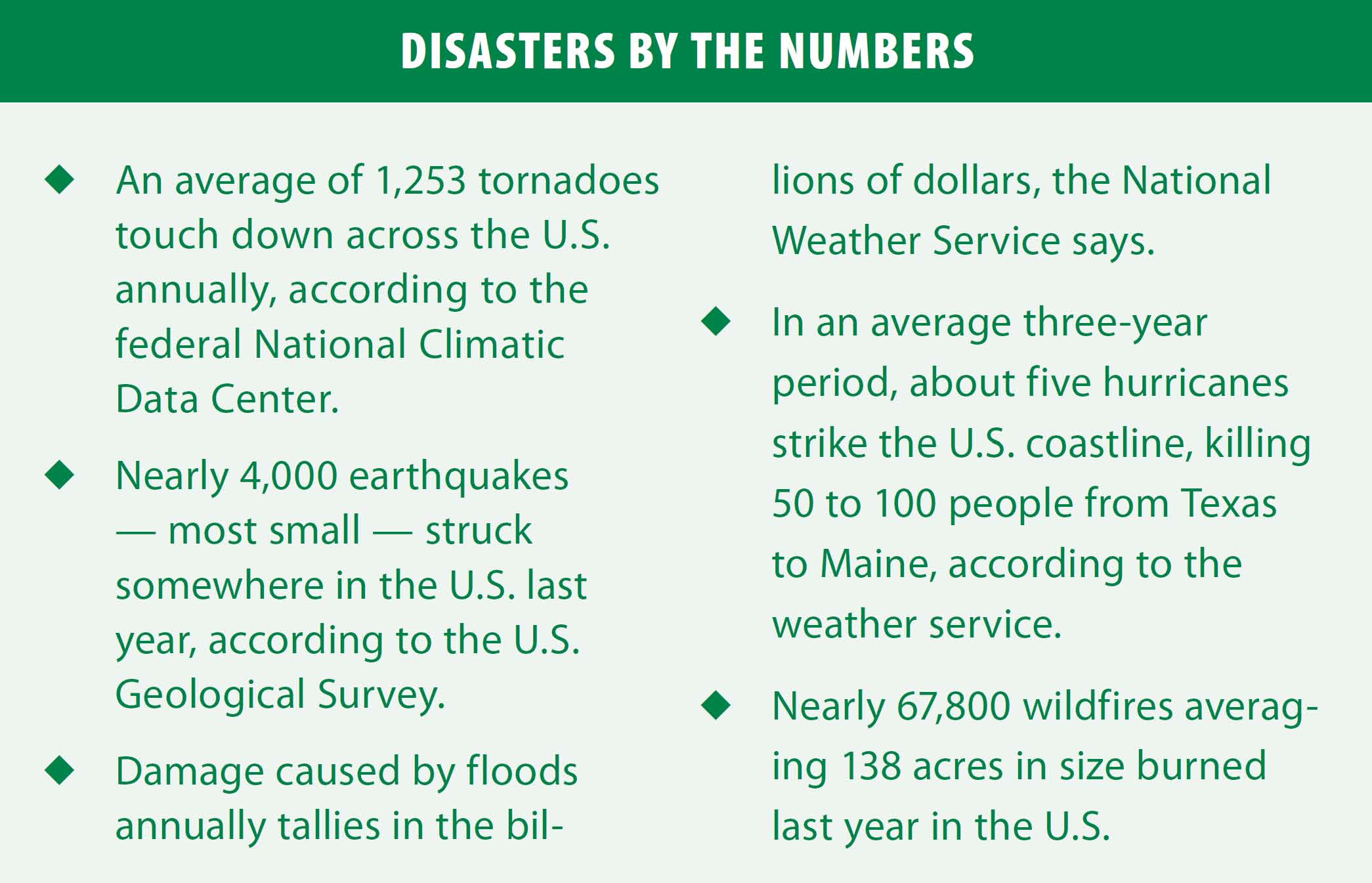

Disaster preparedness isn’t only for earthquakes and hurricanes. It’s also vital for everyday occurrences, such as an extended power outage or sudden wildfire racing over the hill. Every 23 seconds, a fire department rushes to a fire somewhere in the U.S., according to the National Fire Protection Association. Are you ready?

288

Planning is the most important element to keep your cat safe in any disaster. “A common myth is assuming that you are going to be back home in a short period of time. Nobody can predict when you may return after a disaster,” says Gretchen L. Schoeffler, DVM, a specialist in emergency and critical care at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. “It’s obviously a concern if you leave a pet in a house or in a yard that they will run out of food and water. Having to leave them behind evokes images of stranded animals struggling in the floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina. Early implementation of a well-thought out plan might very well mean the difference between life and death for all of your family members, including the furry ones.”

Experts stress that you should:

-Have a plan of action. You may not be with your family when disaster strikes. How you will contact one another? (Text messages often work when phone calls don’t.) What will you do in different situations, such as a tornado or flood? What’s best for you is typically what’s best for your pets, the Federal Emergency Management Agency says. “The likelihood that you and your animals will survive an emergency such as a fire or flood, tornado or terrorist attack depends largely on emergency planning done today.”

-Keep your cat current on vaccinations and rabies shots to ensure he’s healthy and can be accepted at a kennel or emergency shelter if necessary.

-Microchip your cat and register him with the microchip company. Be sure to update your information, including your cell phone, when you move. Less than 2 percent of cats without microchips in animal shelters reunite with their owners, the Humane Society of the United States says, but a study found reunifications soared to 63.5 percent for microchipped cats.

-Have a collar for your cat securely fastened with an ID tag and your phone numbers.

-Designate a willing neighbor or friend to serve as stand-in to evacuate your cat if you’re at work when disaster strikes. Give him a house key and show him where you keep evacuation supplies.

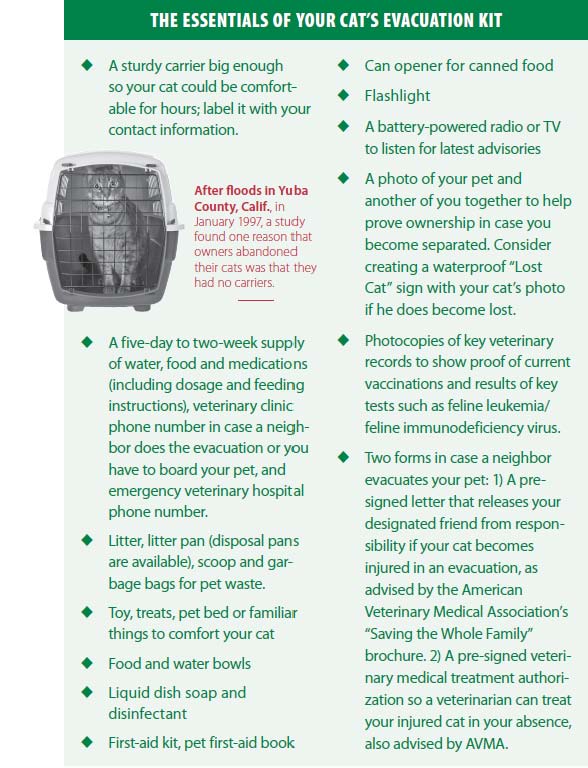

Dick Green, chief of ASPCA disaster preparedness, has led animal rescues, including recovery efforts, during Hurricanes Katrina and Rita with the American Humane Association. The most obvious mistakes he’s seen: Some owners don’t take steps to have the necessary carrier, pet food, water and veterinary vaccination papers, so when they arrive at a safe destination, “They may only have a pet on a leash.”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

288

Others have arrived at emergency shelters and had to sleep outside with their pet because they didn’t identify pet-friendly lodging in advance and the shelters were full, he says. (See GoPetFriendly.com, among other sites.) They also may not have called their local emergency management office, animal shelter or animal control office for advice on whether a last-resort, pet-friendly shelter would be available — pre-registration may be required.

Some evacuees of the 2009 Mississippi River flood in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, had lived in their cars with their pets before a temporary animal emergency shelter opened at Kirkwood Community College and took in more than 1,000 animals. “There are so many common mistakes that are made at that [pre-planning] level,” Green says. When owners try to wing it at the last minute, “They don’t have time to plan properly.”

A better bet: Start now by learning of pet-friendly motels outside your immediate area or lining up relatives who could take you in if you need to evacuate with your pets. Getting to know your neighbors and their pets can also be an advantage in an emergency, Green says. He suggests a block party as a beginning. “We really try to encourage folks to get to know their community. A lot of times, they don’t know their neighbors’ pets.” If for example, a fire erupted while a neighbor is at work, you’d know to tell a firefighter that two cats and a dog are inside.

Training your cat to regard a crate as a safe haven will reduce his stress if he must be caged or crated during an evacuation or emergency treatment at a veterinary clinic. (Some owners have found success with “free-access” training in which you introduce the crate by leaving the door open with treats and toys inside.) “I always say that nobody’s pet should be unhappy in a cage,” says Dr. Schoeffler, who is Chief of Emergency and Critical Care Services at the Cornell Hospital for Animals. “They may need to live in a crate for a period of time or a cage. By not learning to like them, it makes them miserable beyond what they need to be.”

Worse, after the January 1997 floods in Yuba County, Calif., a study found that one reason some people left cats behind in an evacuation was that they had no cat carriers.

No Advance Warning. Disasters that occur without advance warning put pets at special risk, Green says. Wildland fires, earthquakes and tornados are the top three in his view. House fires are an easily forgotten peril, though Dr. Schoeffler sees firefighters, passers-by, neighbors and other family members take pet victims of fires to the Cornell hospital several times a year. “Unfortunately, people living in that house may have been injured themselves and have been transported [for treatment],” says Dr. Schoeffler. “As a result, we’re not dealing with immediate family. We’re dealing with people who are trying to help the family that suffered the loss.”

All of which reinforces the advice that it’s wise to enlist a neighbor to rescue your pets when you’re not home and always keep a disaster kit ready to grab on the run.

400

400

400