Kseniia Soloveva | iStock Photo

Lymphoma is cancer of the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell that produces antibodies and protects your cat from infections. When lymphocytes become cancerous and start dividing out of control, they can go rogue and start to destroy normal tissues too. This is the most common type of cancer in cats, responsible for about 30% of all cancer cases.

Fortunately, lymphoma usually responds well to chemotherapy, which can get your cat back to feeling like her normal self. While many people fear chemotherapy, worrying about side effects, cats seem to tolerate chemotherapy much better than humans do. They rarely experience the nausea, poor appetite, and malaise that some people associate with chemotherapy.

The Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is a network of vessels and tissues that stretches throughout your cat’s entire body. In addition to the lymph nodes and thymus gland, lymph tissue is found in the spleen, liver, heart, kidneys, and bone marrow. The lymph system delivers nutrients to the body, transports wastes and cellular debris, absorbs fat from the intestinal tract, and processes and removes infectious agents.

Lymphocytes often hang out in lymph nodes and the thymus, but also circulate throughout the body via the lymphatic vessels and the bloodstream.

Types of Feline Lymphoma

Lymphoma can show up anywhere. Because lymphocytes can travel through the blood and lymph vessels, lymphoma is considered a systemic disease even if problems are only being observed in one part of the body. Common symptoms include weight loss, poor appetite, and lethargy, but exact symptoms and potential outcome vary based on the primary location of the cancer.

Intestinal or alimentary lymphoma is responsible for 50 to 70% of cases. It often appears in older cats, and exposure to tobacco smoke is a risk factor. Affected cats usually show GI signs such as weight loss, diarrhea, and vomiting. Some cats have a decreased appetite, while others show an increased appetite or no change. Infection with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) can be risk factors.

Other types of lymphoma include:

Mediastinal lymphoma: FeLV is strongly linked to this type of lymphoma, and 80% of cats with it are FeLV positive. Found in the cat’s chest, it was once the most common type of lymphoma in cats, but increased education about FeLV and vaccinations have drastically reduced the incidence of mediastinal lymphoma. This variation typically shows up in cats under 5 years old, and affected cats may have trouble breathing due to fluid buildup in the chest or may vomit frequently.

Renal lymphoma: Affected cats show signs of kidney failure such as weight loss, decreased appetite, increased thirst, and vomiting. The kidneys will often become enlarged. FeLV is a risk factor, and 50% of affected cats are FeLV positive. Renal lymphoma often spreads to the central nervous system and brain, which can result in neurological signs like stumbling, walking in circles, or seizures.

Nasal lymphoma: Cats with lymphoma in their nose often have swelling in their muzzle and face, discharge from the nose, and frequent sneezing. Nasal lymphoma is unique in that it sometimes is completely localized to the one area.

Multicentric lymphoma: In this cancer, lymph nodes throughout the body are affected. You may notice that your cat’s lymph nodes are enlarged when you pet her. Common lymph nodes that owners notice are on the neck under the chin, in front of the shoulder blade, in the armpits, in the groin, and behind the stifles (knees). FeLV and FIV can both predispose cats to this type of lymphoma.

Diagnosis

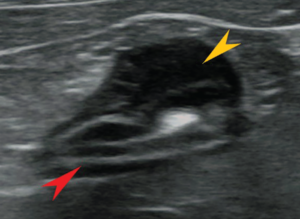

Because of the nonspecific signs that often come with lymphoma, your veterinarian will start by doing a general workup to look for clues to what is causing your cat’s symptoms. This may include a complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, FIV/FeLV test, urinalysis, radiographs (x-rays), and/or an abdominal or thoracic ultrasound.

Once your veterinarian has identified either a tumor or suspicious lymph nodes, she will likely recommend a biopsy or fine needle aspirate (FNA) to get a definitive diagnosis. A surgical biopsy is often best, as it retains the microscopic “architecture” of the tumor, which can help the pathologist determine its most likely cause.

An FNA is the cheapest and least invasive method, however. To do an FNA, the veterinarian will insert a needle into either a tumor or a suspicious lymph node and extract cells for evaluation under a microscope.

Sounds simple, but this method doesn’t always give a definitive answer because the sample FNA provides is small and perhaps not representative of what is going on in the whole tumor. In addition, not all areas of the body are accessible to FNA. That said, FNA can be a good place to start, especially when a full biopsy is not an option.

If a decision is made to seek a biopsy to rule out intestinal lymphoma, an endoscopic biopsy may be an option. Endoscopy requires anesthesia so your cat will sit still while a tiny flexible fiberoptic camera is passed into her gastrointestinal tract to inspect it and to obtain tissue samples, but it is less invasive than obtaining biopsies via laparotomy (surgical incision into the abdominal wall). Biopsies obtained via endoscopy and laparotomy appear to be equally effective at providing useful diagnostic information.

lymphoma in a cat.

Grading

When a sample is sent to a lab for histopathology (analysis under a microscope) and determined to be lymphoma, the pathologist will give it a grade based upon a number of factors, including cell size, appearance, and architecture. The grade indicates how aggressive the cancer appears to be and is useful for determining the best treatment option for your cat and her prognosis.

Low-grade or small-cell lymphomas have cancer cells that divide more slowly. This grade is less malignant and usually more responsive to chemotherapy.

High-grade or large-cell lymphomas have rapidly dividing cancer cells and are more aggressive. These cases are more difficult to treat.

In addition, a reference lab can do special stains on your cat’s blood to identify whether her lymphoma involves T-cells or B-cells (types of lymphocyte), which may affect treatment decisions. The downside is that it can be expensive.

Treatment

Lymphoma is never really “cured.” The goal of treatment is to get the cat into remission, or a state where she has no symptoms of illness and there are so few cancerous lymphocytes in her body that they aren’t detected. The cancer cells are still around, however, and may take off again in the future. Many cats with lymphoma achieve full or partial remission with treatment.

Chemotherapy is the mainstay of lymphoma treatment because it can target cancer cells wherever they are in the cat’s body. The most successful protocols use multiple drugs. This allows the veterinarian to use lower doses of each drug, minimizing side effects, while also attacking the lymphoma from multiple angles. If a cat shows side effects to a medication, your veterinarian will adjust the treatment protocol to ensure her comfort. Approximately 70 percent of cats achieve complete remission for varying periods of time, with a median remission time of 265 days. Cats that maintain full remission for one to two years (about one third of feline lymphoma patients that are treated) may survive for significantly longer periods of time (i.e., years). During complete remission, cats can live high-quality, fairly normal lives.

Some chemotherapy drugs can be administered by mouth in either pill or liquid form, while others are given by injection (usually into a vein). The two most common oral drugs are prednisone/prednisolone (a steroid that has a variety of other uses) and chlorambucil. These medications can even be given at home. Injectable chemo drugs include doxorubicin, vincristine, and cyclophosphamide, and many others that may be used depending upon response, availability, and the potential side effects of each. The exact protocol will depend on your cat’s individual case and your veterinary oncologist’s preferences.

Treatment frequency and duration vary widely based on the protocol being used and how the cat responds to treatment. Oral medications may be given at home daily or every couple days, and some may be given for the rest of the cat’s life. Injectable drugs require a veterinary visit and are usually given less frequently (weekly or every few weeks). Treatment duration can range from six months to two years.

Some cats may need a few rounds of treatment before symptoms improve, but others can get relief as quickly as 24 hours after their first chemo treatment. Remission is achieved in 70% of cats with low-grade intestinal lymphoma treated with chemo and in 25 to 50% of cats with high-grade intestinal lymphoma treated with chemo.

If your cat comes out of remission, or her lymphoma comes back, changing to a different chemo protocol will often be successful in getting her back in remission. If a patient comes out of remission repeatedly, however, her lymphoma may become resistant to all treatment options.

Surgery is generally only useful for debulking large lymphoma tumors whose physical presence are negatively impacting a cat’s health. Surgery will not cure lymphoma.

Radiation therapy can be beneficial in conjunction with chemo in some cases, especially for nasal lymphoma.

Response to treatment can be unpredictable in feline lymphoma. Some cats will, unfortunately, do poorly while others thrive for several years after treatment. The type of lymphoma, how sick your cat is at the time of diagnosis, FeLV status, grade of the cancer, and therapy instituted all play a role in your cat’s outcome, but the only way to know for sure how your cat will respond to chemo is to try it.

However, remember that 50 to 70% of cats respond well to chemotherapy. Life after a diagnosis of feline lymphoma can be comfortable and stress-free for your cat, giving you more quality time together, in some cases for considerable periods of time.

What You Can Do

Bring your cat in for regular veterinary checkups, including bloodwork: once a year for young cats, every six months for cats over 10 years old.

- Keep your cat indoors and away from cats who may be infected with FeLV or FIV.

- Don’t smoke, especially around your cat.

- Vaccinate outdoor and indoor-outdoor cats against FeLV.

- Pay attention to subtle changes in your cat’s health or behavior and report them to your veterinarian.

- Keep all recheck appointments for a cat undergoing chemo or in remission. Chemo can cause bone marrow suppression and make her vulnerable to infections.