Your cat is lethargic, doesn’t want to eat, and may be vomiting or having diarrhea. And his belly hurts. One potential cause is an intestinal blockage.

Intestinal obstructions happen when something that your cat can’t digest gets stuck in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Just like a traffic jam, the foreign object prevents food and other things your cat may have eaten from moving through.

This quickly becomes unpleasant for the cat, and eventually the pressure can cut off circulation to the intestinal tissue and cause it to die. Untreated obstructions can be fatal.

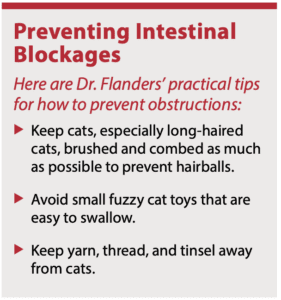

The most common offenders are hairballs and fuzzy cat toys, says James Flanders, DVM, board-certified veterinary surgeon and associate professor emeritus at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

“String, yarn, and tinsel are not as common but are much more concerning,” says Dr. Flanders. “String foreign bodies can become lodged at one end (around the tongue or as a wad in the stomach). The trailing end of the string will move into the intestine and the intestine will try very hard to move the string. If the string stays in place long enough it can actually cut through the wall of the intestine and cause peritonitis, a potentially fatal situation.”

“String, yarn, and tinsel are not as common but are much more concerning,” says Dr. Flanders. “String foreign bodies can become lodged at one end (around the tongue or as a wad in the stomach). The trailing end of the string will move into the intestine and the intestine will try very hard to move the string. If the string stays in place long enough it can actually cut through the wall of the intestine and cause peritonitis, a potentially fatal situation.”

Hair ties and rubber bands are also potentially problematic, especially if your cat eats them frequently.

Diagnosis

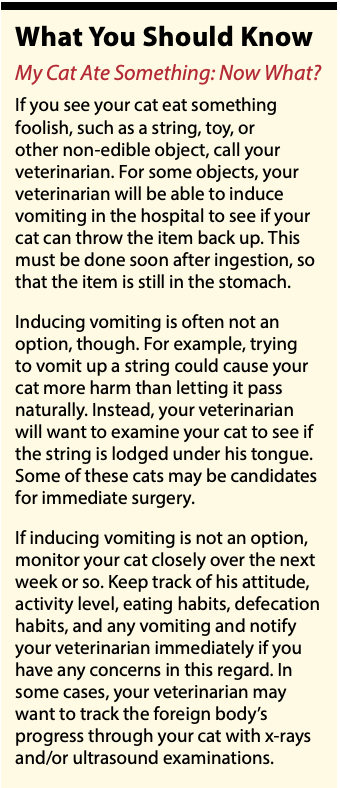

As always, Step 1 is to take your ain’t-doin’-right cat to the veterinarian’s office. Your veterinarian will start with a physical exam to get an idea of your cat’s overall health and palpate his abdomen. They will also look in your cat’s mouth and under his tongue to check for any strings or other linear objects stuck there.

Be sure to tell your veterinarian about anything that you have seen your cat eat recently that wasn’t food, or anything suspicious that he was playing with, even if you didn’t witness him gulp it down.

Be sure to tell your veterinarian about anything that you have seen your cat eat recently that wasn’t food, or anything suspicious that he was playing with, even if you didn’t witness him gulp it down.

Radiographs (x-rays) can often show telltale signs of an obstruction. In some cases, the veterinarian may give your cat barium via his mouth and then take a series of x-rays to see how it moves through his GI tract. An ultrasound of the abdomen may also be helpful.

Your veterinarian will likely also recommend bloodwork both to rule out other potential causes for your cat’s symptoms and to see how his organs are doing. Bloodwork can reveal signs of infection or organ failure that may occur as an obstruction progresses.

Exploratory Surgery

Most intestinal blockages can only be treated with surgery to remove the foreign body. This is often an emergency, because leaving the blockage in place can cut off the blood supply to the intestines and cause them to necrose (die) or perforate.

Your veterinarian will recommend surgery if the radiographs show a definite obstruction or if an obstruction is suspected and no other cause for your cat’s symptoms has been identified. This surgery is often referred to as an “exploratory” surgery because the surgeon doesn’t know exactly what he or she will find.

Depending on the cause of the obstruction, your cat may have several incisions into his intestines. Discreet items like a coin or cat toy can often be removed in a single piece, but long or amorphous items such as a string or large hairball may need to be cut into sections and removed at multiple points.

Depending on the cause of the obstruction, your cat may have several incisions into his intestines. Discreet items like a coin or cat toy can often be removed in a single piece, but long or amorphous items such as a string or large hairball may need to be cut into sections and removed at multiple points.

Once the primary blockage has been removed, the surgeon will examine your cat’s entire intestinal tract, feeling for any smaller items that could cause trouble, and evaluating tissue health.

Necrotic tissue will be removed so that your cat is only left with healthy intestinal tissue.

If your cat’s intestines were perforated because of the obstruction, the entire abdomen will be flushed thoroughly to remove intestinal contents that seeped out. Food bits and enzymes do not belong loose in the abdominal cavity, and leaving them there can cause severe infections such as peritonitis and sepsis, even leading to death.

Once everything has been cleaned up and your veterinarian is satisfied that all potential problems have been removed, they will suture your cat back up.

Medication Support

Most veterinarians will give injectable antibiotics during exploratory surgery to safeguard against any intestinal contents that might leak out. Your cat may also stay on antibiotics after the surgery if he showed signs of infection or your veterinarian is concerned about one developing.

Pain meds should also be expected. Your cat will receive injectable pain medications during the procedure, and then will usually be on them for the first few days after surgery to keep him comfortable.

IV fluid therapy before, during, and after surgery will help to keep your cat hydrated and can maintain electrolytes and blood pressure.

After Care

Your veterinarian will likely want to keep your cat in the hospital overnight after his surgery. This allows the team to monitor him closely during recovery, and to administer additional medications as needed. He will be given small meals and closely watched for any vomiting and to make sure that he is pooping normally.

“Cats usually recover fairly well from simple intestinal surgery, or a single obstruction without peritonitis,” says Dr. Flanders. “Their appetite comes back within one to three days in uncomplicated cases.” Your cat will be able to go home once he is eating on his own and pooping normally.

More severe cases, particularly when the surgeon must remove sections of the intestines due to compromised tissue, have a more guarded prognosis. Ill cats will be kept in the hospital for several days for supportive care. In rare cases, incisions can fail because of weak tissue and the veterinarian may have to do a second surgery.

When your cat comes home, follow discharge instructions carefully. Your veterinarian may have specific criteria for what your cat can eat and how often, and your cat’s activity should be limited so his incision can heal. Stay in touch with your veterinarian to give updates on how your cat is doing.