Mast cell tumors represent one of the most common types of tumors affecting the feline spleen, skin and intestines, yet few studies have focused on determining the optimal treatment for cats. While surgical removal of tumors continues to be the treatment choice for mast cell tumors (MCTs), new research indicates that certain chemotherapy drugs might offer promise for more serious cases of malignant MCTs.

“The true role of chemotherapy for the treatment of feline mast cell tumors is not known,” says Cheryl Balkman, DVM, ACVIM, Senior Lecturer and Chief of Oncology at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. “Chemotherapy is considered in cases where there is metastatic disease (in which the cancer has spread) or if a tumor can’t be surgically removed.”

Treatment Response. Studies have found that about 50 percent of cats with cancerous MCTs respond to treatment with a chemotherapy drug called lomustine, Dr. Balkman says. Another class of chemotherapy drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Palladia, Kinavet) has anecdotally been reported as being effective in treating certain tumors in cats as well. However, to date, no large controlled trial has been done to evaluate the true potential of these drugs.

The incidence and severity of MCTs are much lower in cats than in dogs, which accounts for much of the research into new treatments being focused in the canine realm. In cats, MCTs are the most common splenic (spleen) tumor, the second most common cutaneous (skin) tumor and the third most common intestinal tumor. Treatment and prognosis can vary dramatically based on the location of the tumor or tumors. They can range from benign (non-spreading, non-life-threatening) to malignant (spreading, life-threatening).

Kelly Hume, DVM, ACVIM, an oncology researcher and specialist at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals, urges owners to have any abnormality on a cat’s skin investigated promptly.

A cutaneous MCT might appear as a small, firm, raised bump. The bumps can become itchy and red, often the result of a cat irritating the area. This is because, when aggravated, MCTs can release histamine and other inflammatory substances into surrounding tissues.

Systemic Illness. Often, cats with skin MCTs seem otherwise healthy; however, although more than 90 percent of MCTs in the skin are benign, internal (visceral) tumors often behave more aggressively. Cats might show signs of systemic illness, such as loss of appetite, weight loss and vomiting.

Dr. Balkman recommends that cats with multiple cutaneous MCTs be evaluated for visceral mast cell disease because the skin tumors can be a symptom of internal disease that has spread.

“It is also important to realize that mast cell tumors exist on a spectrum,” says Dr. Hume, adding that treatments appropriate for one pet may not be appropriate for another.

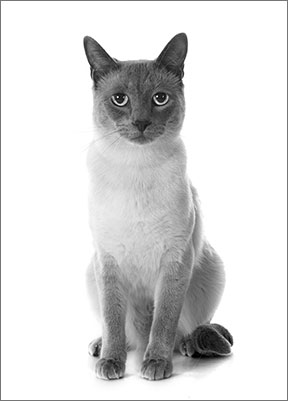

In cats, mast cell tumors are most often seen in the skin of the head or neck, though they can occur anywhere in the body. They’re most common in cats over the age of 4 but have been seen in cats of all ages, including kittens. Siamese cats are at higher risk than other breeds.

Veterinarians typically diagnose MCTs by obtaining cells from the mass via a fine-needle biopsy and performing a microscopic examination (cytology) of the cells. This takes only a few minutes for skin tumors and can often be done without sedation. If a splenic MCT is suspected or an intestinal mass is detected via ultrasound, a needle biopsy can also be performed, though it might require sedation.

If a lymph node surrounding the mass is enlarged, it could indicate that the disease has spread. In such situations, a needle biopsy and cytology might also be performed on the lymph node.

Blood tests can help in MCT diagnosis. The analysis, called a buffy coat test, generally indicates the presence of a mast cell tumor somewhere, but it’s not clear how the finding correlates with its spreading or prognosis. The test uses an anti-coagulated blood sample containing most of the white blood cells and platelets after centrifugation (spinning) of blood — it’s usually buff in color.

“Most solitary mast cell tumors found on the skin of cats behave in a benign manner,” Dr. Balkman says.

“However, cats are more likely than dogs to get primary visceral (internal) mast cell tumors in their spleen.”

Surgical Removal. Most feline skin MCTs are removed surgically, and this is usually curative. A single round of surgery can remove the entire problem.

Cats with internal MCTs can face more complex treatment. Surgical intervention is often indicated. Treatment for splenic MCT often involves splenectomy — the removal of the spleen. Although the procedure is invasive, its effectiveness is well established. “Cats can do quite well, with survival times being over a year in many cases,” Dr. Balkman says.

As previously noted, non-surgical therapy options for feline MCTs also continue to be explored, although published research regarding effectiveness is still limited. The chemotherapy agent lomustine, often recommended for malignant MCTs, has the common side effect of bone marrow suppression. This can lead to a low-white blood cell count and increased susceptibility to infections in cats, Dr. Balkman says.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, approved for use in dogs, are increasingly being used in an off-label manner for cats often in conjunction with surgery; and this mode of therapy may be effective for feline MCT. Common side effects include diarrhea and decreased appetite, although a lowering of white blood cells and increased protein loss through the kidneys can also occur.

“These drugs should be considered true chemotherapy agents, and it is very important that patients receiving these drugs be monitored routinely via physical exam, blood work and urinalysis,” Dr. Hume says. “For owners with pets receiving these medications, it is also important that they communicate any abnormalities they note in their pet to the prescribing veterinarian.”

Preventing Effects. In addition to chemotherapy, cats with MCTs typically receive antihistamines to help prevent side effects from mast cell degranulation (the release of chemicals from within the cells), such as inflammation or stomach ulceration. Steroids are also useful in decreasing inflammation associated with the tumors.

The cost of diagnosis and treatment for MCTs depends on tumor location, number and progression. Fine-needle biopsy and cytology alone can cost approximately $75, depending on the clinic. Surgery fees can range from $250 to $2,500, depending upon the complexity of the procedure. If chemotherapy is indicated, protocol and the size of the patient determine the cost, which often runs $300 to $700 per month. Any additional imaging, such as chest X-rays or ultrasound, would be an additional $200 to $300.

“If owners feel the options presented to them are not feasible, they should consider what is financially feasible and work with their cat’s veterinarian to determine an appropriate course of action within their means. It does not have to be an all-or-nothing approach,” Dr. Hume says, adding that many clinics offer payment plans and financial support.

Likewise, owners of cats diagnosed with MCTs should not despair. Many cats with skin MCTs live for years with appropriate therapy. And although internal MCTs are more complex and invasive, the right combination of therapies enables many cats to live well over a year after diagnosis. As research into new drugs and novel therapies continues, that prognosis is likely to only improve. ❖

HOW MAST CELLS DEVELOP

Mast cells are a type of white blood cell in the immune system. They’re formed in bone marrow and migrate to all the tissues as they mature, concentrated in the skin, respiratory tract and digestive tract.

Mast cells produce a variety of chemicals, including histamines, released in response to stimuli, often inducing an inflammatory response. They are vital to allergic responses and healing.

The actual cause of mast cell tumors is unknown. Like other cancers, MCTs form when mast cells begin to grow and multiply abnormally. Multiple tumors are often present in the skin. They can recur after surgical removal, but it is relatively unusual for them to spread to other parts of the body. Mast cell tumors of the skin are always considered malignant.