The first time you see a cat battling vestibular syndrome, you may be taken aback. The cat may circle around oddly, fall to one side, and may show a head tilt. Nystagmus—unusual eye movements where the pupils rapidly up and down—pretty much makes the diagnosis. Vestibular syndrome is most often seen in older cats, and it usually comes on without warning.

Some cats will roll frequently for 24 to 48 hours. Not surprisingly, nausea and vomiting may follow from the vestibular disturbance. The syndrome can last for two to three weeks and then, just as mysteriously, resolve on its own. Your job is to ensure your cat doesn’t get hurt during an episode and to understand that the syndrome is anything but pleasant for your cat. (Note: Female cats in heat will often roll excessively and vocalize, too, but this activity is not related to vestibular disease.)

What Is It?

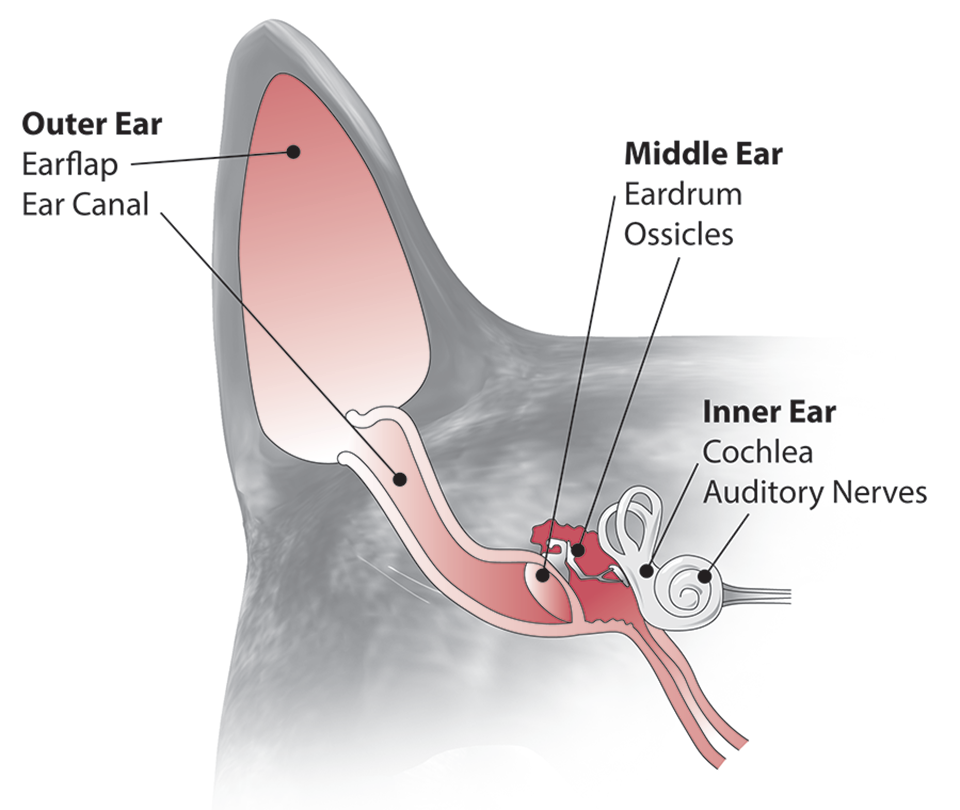

The vestibular system is in involved in balance. An important part of this system, called the cochlea, is located within the inner ear. It communicates with a part of the brain called the medulla, located in front of the cerebellum at the top of the spinal cord, to coordinate balance, including that of the eyes. The cerebellum controls overall body movement and coordination, but is not normally involved in vestibular syndrome’s odd movements.

Diagnosis

If you contact your veterinarian at the first signs of this syndrome—as you should—he/she will do a physical examination, including a neurological evaluation and a thorough ear exam, and will check for nasopharyngeal polyps in the back of the cat’s throat (ear infections and nasopharyngeal polyps are considered possible causes). Cats with bad ear infections that require anesthesia and a thorough cleaning may shows signs for a day or two post cleaning from the ear manipulations.

For most cats, the cause of vestibular syndrome is unknown, and the problem resolves on its own, although it can recur. Advanced diagnostic testing—such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cerebrospinal fluid analysis, or computerized tomography (CT)—is usually only recommended for cases that don’t resolve.

In many areas of the country, feline vestibular signs show up most commonly in late summer, often in young, healthy cats with access to the outdoors.

Some antibiotic drugs, particularly the aminoglycosides such as gentamycin, can cause hearing or balance issues as a side effect. This effect is usually temporary but can be permanent. Metronidazole has been associated with temporary vestibular signs in cats. Lead poisoning, while not as common as it was decades ago, is another potential cause of the syndrome.

Vestibular syndrome that does not resolve may be due to a variety of diseases in the middle ear and/or central nervous system.

Treatment

Treatments target symptoms. The nystagmus may make some cats nauseous, prompting a prescription from your veterinarian for antiemetics (anti-nausea medications) such as maropitant citrate (Cerenia). You will be advised to encourage your cat to keep eating and may have to give your cat subcutaneous fluids to help prevent dehydration.

Any cat with an ear or other body infection that might contribute to or cause the vestibular signs must be treated with antibiotics.

Safety First

Keep your cat confined so she won’t fall down steps or off a balcony or couch. She may require assistance with elimination, starting with getting to the litterbox. Confinement to a crate with soft bedding to cushion any falls is ideal.

The nystagmus and rolling around tend to clear up in just a few days. The ataxic movement, circling, and head tilt may take longer, but generally both problems are back to normal in two weeks or so. If these signs don’t resolve in a couple of weeks, however, more advanced diagnostics may be a wise choice for your cat.

Cerebellar Problems in Kittens

A separate vestibular type of problem that manifests as ataxia (loss of control of body movements) in kittens is cerebellar hypoplasia, which means the cerebellum is smaller than it should be and not properly developed. The most common cause is exposure to or infection with feline panleukopenia virus in the queen during pregnancy. This condition won’t progress but also won’t improve. It is not painful.

Cerebellar hypoplasia becomes evident when kittens start to become mobile. Affected kittens show abnormal movements such as swaying, hypermetria, or goose stepping, and often head tremors. The tremors may intensify when the kitten makes purposeful actions such as attempting to eat, called intention tremors. Luckily, these kittens are not infectious or in any discomfort. With some extra supervision and care in their environment, these kittens can go on to have full and happy lives (see our August 2021 article “Cerebellar Hypoplasia Tremors” for more information, available at catwatchnewsletter.com).