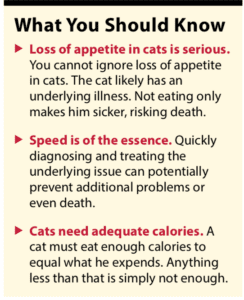

A cat who stops eating may be headed down a dangerous path. While one might think a cat can live on its body fat for a while, it’s simply not true. When a cat starts taking in too few calories, the feline body begins to rapidly break down stored fat, setting the stage for serious liver disease.

“Loss of appetite is one of the most common reasons we see sick kitties,” says Cornell graduate Lisa Markham, DVM, an associate at VCA Fairmount in Syracuse, N.Y. “Cats stop eating for a multitude of reasons. It’s our job to figure out why, treat the underlying cause, and most importantly make sure adequate nutrition is provided until the patient feels well enough to eat on its own.”

Anorexia is a complete lack of appetite. Hyporexia is a diminished appetite. Both are bad, bad, bad in cats. When a cat goes into a negative calorie balance—ingesting fewer calories than are expended—muscle mass is lost, immune function is decreased, wounds don’t heal, intestines don’t function properly, and secondary life-threatening disease can result.

Causes of inappetence in cats include:

Neurologic (you may notice a loss of sense of smell, impaired cognition, depression, the inability to pick up or swallow food)

Physiologic (battling metabolic disease, cancer, infection, cardiac/respiratory disease, constipation, dehydration, nausea, pain)

Environmental or emotional (experiencing stress associated with moves/changes in the home, introduction of another cat, inability to comfortably reach food, unpalatable diet changes)

Behavioral (food aversion sometimes develops when cats associate the sight or smell of food with feeling unwell)

When Trouble Starts

It’s important to seek veterinary intervention as soon as you notice your cat not eating well. The longer it goes on, the worse the potential consequences. This is especially true for overweight cats, who are prone to developing a life-threatening situation called hepatic lipidosis, or fatty liver disease.

“Obese cats who become anorexic can get into trouble within a few days,” says Dr. Markham. “Hepatic lipidosis occurs when large amounts of fat are mobilized too quickly, overwhelming the liver’s ability to process it. This secondary disease is often worse than the original cause of the anorexia and can result in death of the patient.”

Signs of hepatic lipidosis include:

- anorexia

- lethargy

- weight loss

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- jaundice (yellow skin, gums, tongue, whites of the eyes)

Prevention

Preventing the serious consequence of anorexia means getting an adequate amount of food into the cat one way or another. The key word here is “adequate” amounts, which means enough to meet the cat’s daily resting energy requirement (RER). Fortunately, there’s a formula for this. For adult cats it’s RER = [30 x body weight in kg + 70]. For the average 10-pound cat, this computes to 206 calories per day.

On average, there are 100 calories in a 3.5 oz. can of cat food. So, a 10-lb. cat must consume at least two full cans a day to prevent a negative calorie balance.

“While we are working the patient up to try and determine the cause of the anorexia, we initiate treatments geared toward increasing appetite and nutrient consumption,” says Dr. Markham. “Cat owners often say to me ‘Well, she’s eating a little’ or ‘He licks up the juice.’ Unfortunately, this isn’t going to cut it. We have to do better.”

Enticing the Cat to Eat

“Even if the cat is supposed to be eating a specific prescription diet, it’s OK to offer something else in this situation,” says Dr. Markham. “We’d rather have them eat something, than not eat at all.” You can:

Offer different types of canned or dry food, or a combination of both.

Try warming the food just a little to bring out the aroma.

Adding broth or a cooked egg will sometimes entice a reluctant patient.

Sprinkling catnip on the food sometimes helps.

Deli-meat turkey and shrimp can appeal to some cats.

If your cat sniffs at the food, but then walks away, don’t leave it out. This could result in food aversion. Take it away and offer a fresh sample later.

“You can try syringe-feeding liquefied food at home,” says Dr. Markham, “but this is usually pretty stressful for both you and your cat, and you are not likely to get them to take in enough to turn around the negative calorie balance.”

A better approach at this stage is trying appetite-stimulating medications your veterinarian can prescribe. Capromorelin (Elura) is a liquid given orally on a daily basis. It mimics the action of a natural hormone involved in feelings of hunger.

Mirtazapine, an anti-depressant for people, works well for appetite stimulation in cats. It comes in pill form or an easy, effective transdermal preparation (brand name Mirataz) that you can rub on the inside of the ear once a day. Cyproheptadine, an antihistamine that stimulates appetite in cats, is an option, but it’s less popular as it is a pill that must be administered twice a day.

Feeding Tubes

If none of these things get your cat to eat enough, the next step is feeding tubes. For short-term feeding, your veterinarian may try a tiny tube passed through a nostril down into the esophagus (nasoesophageal tube). This is not the best option—many cats absolutely hate it—and only small amounts of thin, liquid food can be administered at a time.

A better option is a larger tube that is surgically placed in the esophagus and extends to the stomach (esophagostomy tube or E-tube). Anesthesia is needed for placement, but cats tolerate these tubes much better and it’s easier to get more food in them through the larger tube. E-tubes can safely stay in place for an extended period. Cats with E-tubes can also eat and swallow food on their own initiative with no problem. The most common indication for E-tubes in cats is for hepatic lipidosis.

“When anorexic cats develop secondary hepatic lipidosis, their livers are failing,” says Dr. Markham. “The only way to stop this devastating process is to provide enough calories to stop the mobilization of fat that is damaging the liver, so the liver can start to heal. Unfortunately, most cats don’t feel well enough to eat enough while waiting for liver function to return. For this reason, feeding tubes become a necessity. Many cats with hepatic lipidosis will die without this life-saving intervention.”

Unfortunately, just putting out free-choice food, with everyone in the house refilling it “as needed,” is not a great system. One person should monitor the cat’s food intake. With more than one cat sharing food bowls, your job becomes even more difficult. Watch as best you can who is eating when and what and keep your eye out for signs of trouble.ν