It’s not fun when you get something in your eye. A tiny eyelash feels like a giant log. Worse, if it gets in there while you’re sleeping and unaware, it might mean a painful corneal abrasion or ulcer when you wake up in the morning.

It’s no different for your cat. Any foreign material that gets in the eye is painful and can cause damage. Hair and lint are common offenders. Grass, seeds, plant awns, and tiny bugs are frequent offenders for outdoor cats.

Your cat’s eye has natural mechanisms for taking care of small matter that gets in the eye. These include increasing tear production to flush it out, reflex blinking to move the matter, and a mobile “third eyelid” called the nictitans that offers protection for the cornea and helps keep the eye moist.

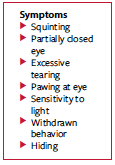

If these defense mechanisms don’t resolve the problem, your cat will show signs of discomfort, including squinting, a closed eye, excessive tearing, pawing at the eye, sensitivity to light, withdrawn behavior, or being prone to hiding.

First-Aid

First-aid involves flushing the eye with a commercial eye wash solution (human products are fine to use) or saline. If you can see foreign material, focus your efforts there. If you successfully move the offending material close to the eyelid margin, you may be able to drag it out using a moistened cotton ball. Once you’ve done this, if your cat seems comfortable again, you’re set.

are fine to use) or saline. If you can see foreign material, focus your efforts there. If you successfully move the offending material close to the eyelid margin, you may be able to drag it out using a moistened cotton ball. Once you’ve done this, if your cat seems comfortable again, you’re set.

If there’s corneal damage, you may notice a bluish cloudiness to the normally clear cornea, and your cat will continue to be uncomfortable. This means a trip to the veterinarian’s office. Any painful eye condition is considered a potential emergency, as superficial injury can rapidly progress to deeper damage. The risk in waiting is loss of vision or irreversible damage resulting in loss of the entire eye. Expect to be seen that day. If your regular vet has no availability, see your local urgent care/emergency veterinary facility.

Your veterinarian will usually use a topical anesthetic to better evaluate the entire eye, including underneath the eyelids and nictitans, potentially discovering foreign material inaccessible to you at home. A fluorescent stain may be placed in the eye. This stain is drawn to any corneal injury, and the spot “lights up” in the eye upon illumination with a black light.

If corneal injury is identified, this is usually treated with antibiotics and pain medicine, with a follow-up visit in one to two weeks to confirm healing.

Penetrating Injury

A penetrating ocular foreign body is a much worse situation. Penetrating foreign bodies puncture the cornea. Sometimes they just puncture and don’t stick around, like a pin prick. Other times, they puncture and stay stuck in the cornea. Either way, it’s bad and an emergency. Examples of offending agents include cat claws, splinters, twigs, porcupine quills, and sewing needles.

If the cornea is penetrated in this way, intraocular inflammation is inevitable and infection is likely. When a foreign body punctures the cornea, it enters the anterior chamber of the eye (the area between the cornea and the iris), immediately causing anterior uveitis. Uveitis is inflammation of the middle layer of the eye, which includes the iris (the visible colored portion of the eye surrounding the pupil). Signs of uveitis include pain, cloudiness or visible blood inside the anterior chamber, and a constricted pupil. Sometimes the iris will look swollen or discolored.

The deeper the penetration, the more likely the lens and posterior chamber of the eye are to be damaged or infected, which worsens the prognosis both for saving vision and, possibly, for saving the eye. Additionally, cats who suffer traumatic injury to the lens capsule are prone to subsequently developing cancer in that eye (intraocular sarcoma), another strike against a good prognosis.

If your veterinarian sees an embedded corneal foreign body, or suspects there has been a penetrating corneal injury, you will likely be referred to a veterinary ophthalmologist for specialized care. If the corneal wound is big enough, and the eyeball is otherwise intact (i.e., not collapsed) surgery to suture the wound closed may be indicated. Antibiotics and pain management are important aspects of treatment of these injuries.

Because severe penetrating eye injuries are difficult to treat successfully, long-term complications like recurrent uveitis and glaucoma (elevated pressure within the eye) are common, and the prognosis for saving vision is guarded to poor. Enucleation (removal of the eye) is frequently recommended and is often the best option in advanced cases. If treatment is elected and fails, enucleation becomes the only remaining option.