With the depths of winter upon the northern states, frostbite is a threat for cats who venture outside. When our cats are exposed to the cold, their bodies prioritize keeping their internal organs warm. The blood vessels in their extremities—legs, ears, and tail—constrict, decreasing the blood flow in those areas to divert it to their core. In the short term, this is a great strategy. But over time, the tissues with decreased blood flow are more vulnerable to freezing.

Who’s At Risk

Brief outings into the cold are relatively low risk for most cats. Frostbite becomes a concern in extreme cold temperatures or if the cat has prolonged exposure to the cold. Being wet or damp and wind chill factors increase risk.

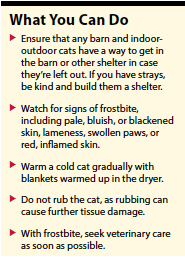

Barn cats often do well, as they come and go as they please and have ready access to shelter, but be sure they are inside when closing the barn up at night, or make sure there is a kitty access area.

House cats who get out by accident and strays who do not have a home are at higher risk. Indoor cats are often scared when they end up outside and more worried about avoiding predators than staying warm. They also are not accustomed to cold temperatures and may have a thinner undercoat because of being used to a heated house.

House cats who get out by accident and strays who do not have a home are at higher risk. Indoor cats are often scared when they end up outside and more worried about avoiding predators than staying warm. They also are not accustomed to cold temperatures and may have a thinner undercoat because of being used to a heated house.

Cats with health conditions that decrease circulation, such as diabetes or heart disease, are at increased risk of frostbite and can sustain tissue damage more quickly than healthy cats. Kittens and senior cats with minimal body fat are also at increased risk.

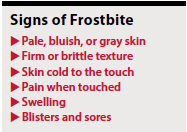

As frostbite progresses, the frozen tissue will die, turn black, and slough off. This process can also lead to secondary infections because of the damage caused by inflammation of the tissue.

It can take several days to truly assess the extent of the damage from frostbite. Even if caught “in time,” the affected areas will usually swell as the tissues thaw and will be painful and inflamed.

Treatment

If you are suspicious of frostbite in a cat, the first step is to get him warm and dry. Use warm towels right out of the dryer if available and wrap the cat. Pat him dry. Avoid rubbing the areas, as this action can cause additional damage to the compromised tissues.

Veterinary care is recommended. The veterinarian will do a thorough exam to get an initial estimate of the damage and may run bloodwork to check for signs of organ failure in severe cases. Any sores will be cleaned and treated as appropriate. Antibiotics may be given to prevent infection as the body deals with the damaged tissues, and pain medications will be given as needed.

Once the cat is warm, dry, and stable, he will be monitored for several days. He might be able to go home with you and just come in for checkups, or he may need to stay in the hospital. Dead tissue may need to be debrided (removed) over the next week or two. In severe cases, the cat may require amputation of the affected body part or may even die.

The cat may need to wear an Elizabethan collar (cone) at points during the recovery process to prevent him from chewing at the affected areas. Think of the sting as your hands warm up after being outside in the cold!

Thankfully, frostbite is relatively rare for our pet cats. But if you do suspect frostbite in your cat or a stray that you have found, seek veterinary care as soon as possible. Prompt treatment for frostbite is the best option to preserve the cat’s limbs and extremities.

Thankfully, frostbite is relatively rare for our pet cats. But if you do suspect frostbite in your cat or a stray that you have found, seek veterinary care as soon as possible. Prompt treatment for frostbite is the best option to preserve the cat’s limbs and extremities.