These are dreaded words for a veterinary clinic: “We have a blocked cat coming in.” A “blocked cat” is vet clinic jargon for a cat with a urethral obstruction (UO). Because UO is a painful, potentially life-threatening condition, a blocked cat always takes precedence over less urgent appointments on the schedule.

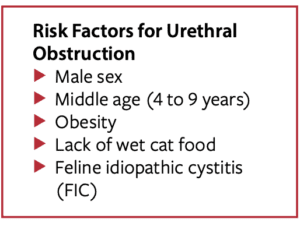

UO can be caused by stones, urethral plugs composed of cellular material, tumors, or urethral strictures (anatomic narrowing of the urethra) and is more common in male cats than females due to their smaller urethral diameter.

Signs of UO are initially easy to overlook, including spending excess time in the litterbox posturing to urinate unsuccessfully, straining to urinate, excessive licking of the genitalia, and vocalizing while trying to urinate. If you notice any of these things, get your cat to the vet right away.

911 Emergency

If these initial symptoms aren’t noticed, things can progress quickly from bad to worse. Once the bladder is fully distended with urine, continued urine production can result in urine backing farther up in the urinary tract, potentially all the way to the kidneys, which can be irreparably damaged (a process referred to as hydronephrosis). If the obstruction isn’t relieved quickly, the bladder may rupture.

Clinical signs in cats that experience UO for prolonged periods may include depression, vomiting, and inability to stand/walk around.

Either way, serious metabolic derangements can ensue, resulting in electrolyte disturbances, decreased urine production, the buildup of toxins in the bloodstream (azotemia/uremia), cardiac arrhythmias, shock, and, if not treated appropriately, death.

An increased urine production after an obstruction is relieved (referred to as post obstructive diuresis) may predispose to dehydration if not addressed appropriately. It can take as little as 24 hours for problems to develop, so quick diagnosis and intervention is essential.

Treatment of UO

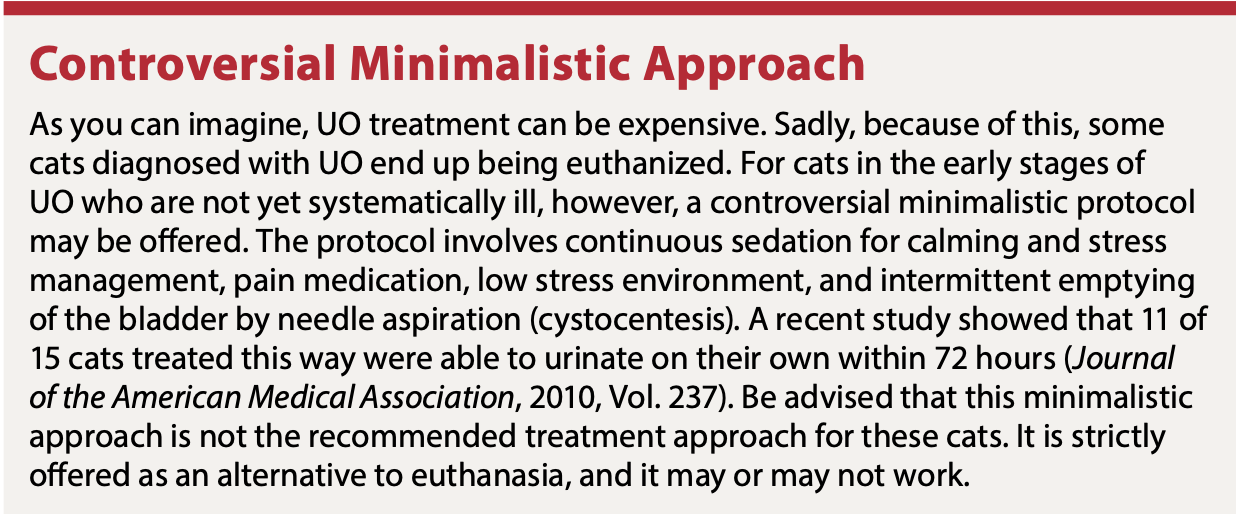

Treatment of UO involves heavy sedation or anesthesia to manually unblock the urethra, placement of an indwelling urinary catheter that usually remains in place for up to three days, hospitalization, fluid therapy, pain management, medication to relax the urethra, and possibly antibiotics.

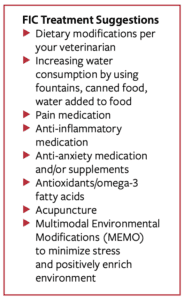

The diagnostics performed while your cat is hospitalized may include urinalysis to check for crystals and evidence of infection, urine culture to confirm infection, bloodwork to monitor kidney function and electrolytes, and X-rays and/or ultrasound to check for bladder or urethral stones. If stones are identified, surgery or stone-dissolving diets may be recommended. If no stones or urethral plugs are identified, feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) may be the cause of your cat’s UO (see sidebar for FIC treatment suggestions).

Repeated Blocks

Cats who experience recurrence of UO (rUO) become candidates for a surgery referred to as perineal urethrostomy, during which the urethra in the penis is modified to create a larger urethral opening. This allows tiny stones/crystals and cellular debris to pass more easily, with the goal of preventing future blockages.

There may not be a lot you can do to keep your cat from re-obstructing, says Dr. Jethro Forbes, assistant clinical professor in emergency and critical care at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

“After going home, there are few if any obvious interventions that have the evidence for reducing the risk of rUO,” says Dr. Forbes.

“Historically, prazosin, a medication used to reduce urethral spasm, had support, but a couple of studies have shown no benefit in reducing rUO rates, and we know medicating cats is stressful. Steroids and NSAIDs are not supported with any evidence for benefit and may cause harm. We do send most of our UO cats home with gabapentin as an anxiolytic with analgesic properties, but this has not been shown to definitively improve outcomes,” he says.

“Reduction of stress and any precipitating stressful environmental influences is a less evidence-based recommendation, but has some logic behind it,” says Dr. Forbes.

“The one piece of evidence for reducing risk of rUO comes from the pet food companies, with urinary diets (especially stress-controlling diets) showing the most promising evidence for reducing the risk.”

Prognosis for UO

While all of this is horrible, the good news is that the prognosis for UO with prompt, appropriate treatment is good, with greater than 90% of treated cats surviving to discharge. Between 15% and 40% of cats will experience rUO, usually within the first 48 hours of having their UO removed, so careful monitoring at home is critical.

Many cats will continue to show signs like straining to urinate for days to weeks after UO. This can be very disconcerting when you’re worrying about recurrence of a blockage. When in doubt, have your veterinarian examine your cat. Other lingering issues that can occur after relieving UO include bloody urine, urinating small amounts more frequently, and urinating outside the box.

Bottom Line

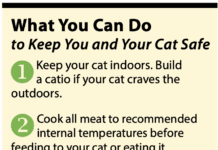

Clearly, the prevention of urinary obstruction in your cat is far better than treatment. Management options to help protect your cat from UO include:

- Keep your cats at a healthy weight.

- Follow your veterinarian’s dietary recommendations.

- Feed canned food or add water to dry food (this helps create more dilute urine, which minimizes urinary crystal formation).

- Follow all recommendations for treatment of FIC if your cat is affected.

- Have your cat examined by your veterinarian at least once a year (twice a year for cats 10 years of age and older).

Doing everything you can to avoid this potentially life-threatening problem is well worth the effort.

Lena DeTar, DVM, is a board-certified shelter medicine veterinarian and interim director of Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine.